For high-quality small lenses, neural nano-optics is developed.

Over the last several decades, the reduction of intensity sensors has made cameras widespread in a variety of applications, including medical imaging, mobile smartphones, security, robotics, and autonomous driving. Smaller order-of-magnitude imagers, on the other hand, might open up a slew of new possibilities in nanorobotics, in vivo imaging, AR/VR, and health monitoring.

Additionally, the rich modal characteristics of meta-optical diffusers can support multifunctional capabilities beyond what traditional DOEs can do (eg, polarization, frequency, and angular multiplexing). Meta-optics can be fabricated using widely available integrated circuit foundry techniques, such as deep ultraviolet lithography (DUV), without multiple steps of etching, diamond turning, or grayscale lithography, such as those used in polymer-based DOEs or in binary optics. Because of these advantages, researchers have exploited the potential of meta-optics to construct flat optics for imaging5,6,7, polarization contro8, and holography9.

Existing metasurfaces imaging methods, however, suffer from an order of magnitude greater reconstruction error than that obtainable with refractive composite lenses due to severe wavelength-dependent aberrations that result. discontinuities in their allocated phase 2,5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.Dispersion engineering aims to mitigate this by taking advantage of group delay and group delay dispersion to focus broadband light 15,16,17,18,19,20,21, however, this technique is primarily limited to aperture designs of ~ 10s of micron22. Therefore, existing approaches have not been able to increase the achievable aperture size without significantly reducing the numerical aperture or the range of wavelengths supported.

Other solutions tried are sufficient only for discrete wavelengths or narrowband illumination11,12,13,14,23 Metasurfaces also exhibit strong geometric aberrations which have limited their utility for wide-field imaging. vision (FOV) Approaches that support a large FOV typically rely on small entry apertures that limit light collection24 or use multiple metasurfaces11, greatly increasing the complexity of fabrication.

Outcome

Model of a differentiable metasurface proxy

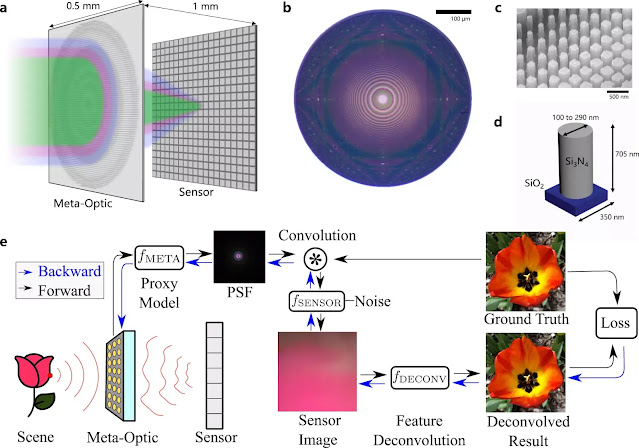

The proposed differentiable metasurface imaging model (Fig.1e) consists of three sequential steps using differentiable tensor operations: metasurface phase determination, PSF simulation and convolution, and sensor noise. In our model, the polynomial coefficients which determine the phase of the metasurface are optimizable variables, while the experimentally calibrated parameters characterize the reading of the sensor and the distance from the metasurface of the sensor are fixed. Our ultra-thin meta-optics learned as shown in (a) has a thickness and diameter of 500 m, allowing the design of a miniature camera. The optics produced are illustrated in (b). A zoom is shown in (c) and the dimensions of the nano post are shown in (d). Our end-to-end imaging pipeline illustrated in e is composed of the proposed efficient metasurface imaging model and feature-based deconvolution algorithm. From the optimizable phase profile, our differentiable model produces spatially varying PSFs, which are then patch convolved with the image input to form the sensor metric. The sensor reading is then deconvoluted using our algorithm to produce the final image. The above illustrations “MetaOptic” and “Sensor” in (e) were created by the authors using Adobe Illustrator.